AI systems & GDPR rules – How do they fit together? – Part I

Starting from August 1, 2024, we are beginning a new chapter in terms of technology governance, marked by the entry into force of the European Regulation on artificial intelligence (the “AI Act” or the “Regulation”)[1]. The AI Act marks a pivotal moment in in how we conceptualize, develop, and deploy artificial intelligence (“AI”), aiming to achieve a delicate balance: promoting technological advancement while safeguarding fundamental human rights.

In this article, wrote by our colleagues Bianca Ciubotaru, Associate, and Silvana Curteanu, Associate, we aim to explore the intersection between AI innovation and big data use with personal data protection compliance, particularly under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)[2]. Our analysis is structured in three parts:

1. In this first part, we shall assess the data protection background and its algorithmic readiness by overviewing the main relevant GDPR provisions related to the development and deployment of AI, and how the AI Act impacts the GDPR’s rules.

2. In the second part, we shall delve deep into the most significant topics concerning the AI & GDPR combo within the employment relationships and the requirements incumbent on the employer as a data controller and deployer when using AI tools.

3. In the third and final part, we shall discuss the importance of human involvement in AI processing activities, and the classification as „high-risk” systems of certain AI tools used in the employment areas, before wrapping up and laying down our conclusions.

AI Act – From ink on paper to real-world

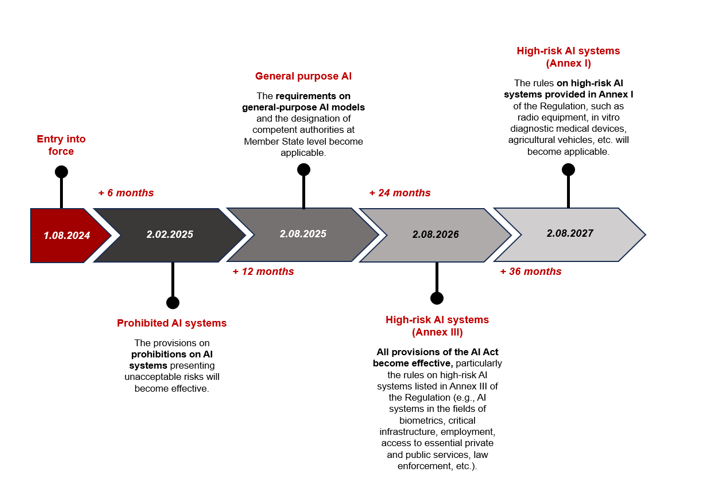

The journey of the AI Act from ink on paper to real-world impact unfolds through a series of meticulous steps, and the effective application of its provisions will then take place in four stages, as follows:

Who falls under the purview of the AI Act?

The AI Act applies to a broad range of entities involved in developing, deploying, and using AI systems within the European Union (“EU”). Specifically, it applies to:

AI Providers: organisations and individuals placing on the market AI systems or general-purpose AI models in the EU, irrespective of whether those providers are established or located within the EU or in a third country;

AI Deployers: entities that use AI systems in their professional activities, including businesses, public authorities, and other organisations, particularly when using high-risk AI applications, that have their place of establishment or are located within the EU;

AI Providers and Deployers: entities that have their place of establishment or are located in a third country, where the output produced by the AI system is used in the EU;

▸ Importers and Distributors of AI systems placing AI systems on the EU market;

▸ Product manufacturers placing on the market or putting into service an AI system together with their product and under their own name or trademark;

Exemptions

The AI Act does not apply in case of:

▸ systems that do not qualify as AI (g., technologies that do not involve machine learning, natural language processing, or similar AI techniques);

▸ military applications used exclusively for military purposes;

▸ research and development activities that imply the use of AI systems solely for research and development purposes, particularly in a non-commercial context;

▸ personal use: AI systems used by individuals for personal, non-professional purposes (g., personal assistants or home automation systems that do not impact others);

▸ certain public services that do not involve high-risk AI applications, depending on the specific context and use case;

▸ small enterprises: while the AI Act applies to all organisations, there may be certain provisions or requirements that are relaxed or not enforced for small enterprises, particularly in terms of compliance burdens;

▸ free and open-source software (unless their use would classify them as a prohibited or high-risk AI system, or their use would subject them to transparency obligations).

As AI tools become increasingly integrated into our daily activities, ensuring compliance with the GDPR is paramount. The interference between the GDPR rules and AI Act provisions is essential, given that the AI Act also provides a framework for a new category of so-called general-purpose AI models[1] – the typical examples of such a category are the generative AI models, which are characterized by their ability to easily respond to a wide range of distinct tasks and, some of them, on their self-train capability.

Yet, the looming question remains: Will the majority of human tasks be automated by AI? Can AI enhance or replace human reasoning and empathy? Or is a harmonious coexistence possible?

A GDPR perspective – general outlines

As it can be easily observed, the GDPR is AI-neutral and does not specifically regulate the collection and processing of personal data by AI systems. The AI Act complements the GDPR by establishing conditions for developing and deploying trusted AI systems, introducing some novelties related to personal data and certain processing activities.

Regardless of the type of activity they carry out which involves using AI systems or tools, AI providers and deployers shall be required to map their obligations very carefully, particularly considering the interactions between the GDPR and the AI Act and their combined applicability. For example, both regulations address the concept of “automated decision-making” but from different angles, which are undeniably intertwined.

Similarly, while AI models are trained with large amounts of data, the GDPR addresses large-scale automated processing of personal data. Specifically, profiling and automated decision-making processes are some of the key privacy issues within the use of AI to provide a prediction or recommendation about individuals (this subject will be further detailed in Part III of our article).

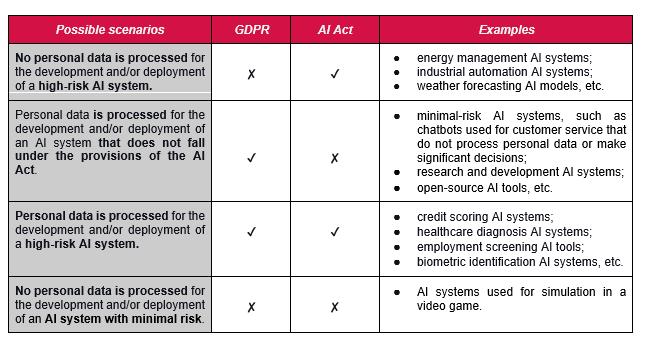

But how do we know which regulation applies in specific cases?

In a nutshell, the AI Act applies exclusively to AI systems and models, and the GDPR applies to any processing of personal data. Thus, there can potentially be four scenarios:

The impact of the AI Act on data protection

Although the objective of both frameworks is a common one – to protect the fundamental rights of natural persons (including the processing of personal data by AI systems lawfully) – there are inevitably certain “tensions” between the provisions of the GDPR and the AI Act.

At first glance, it might seem challenging to align the principles of purpose limitation, data minimisation and the restrictions on automated decision-making processes provided by the GDPR, on the one hand, with the processing of vast quantities of personal data for insufficiently precise purposes in the context of the AI Act’s scope, on the other hand.

Nevertheless, data protection principles can be interpreted and applied consistently with the benefits of AI techniques and the use of big data, for example[1]:

▸ the principle of purpose limitation allows the re-use of personal data when compatible with the original purpose;

▸ the principle of data minimisation might be applied by reducing the identifiability of data rather than the quantity, for example, through pseudonymisation;

▸ the GDPR’s prohibition of automated decision-making comes together, generally, with specific nuances and exceptions, thus not hindering the AI’s further development or deployment in this respect.

Gaining a comprehensive approach to both frameworks is crucial in fostering a culture of compliance, transparency and trust in various sectors of activity (including among employees and employment relationships). Balancing privacy and technological innovation is an attainable goal, and there is a significant complementarity between the GDPR and the AI Act.

Briefly, the most relevant elements of the GDPR that can be interconnected with the use of AI systems or other related automated technologies (including in the context of employee`s data processing activities – this subject will be further detailed in Part II of our article) are:

(i) the right to be informed & the right of access

Articles 13, 14, and 15 of the GDPR require data controllers to provide detailed information about their processing activities, particularly when using automated decision-making or profiling. This includes explaining the logic behind such processes and their potential consequences for individuals. Similarly, the AI Act emphasizes transparency concerning both the development and use of AI systems. The transparency measures in the GDPR are complemented by additional requirements in the AI Act, reinforcing the need for clear information about AI-related data processing, such as:

▸ AI providers must inform individuals when they interact with an AI system if this interaction is not immediately apparent;

▸ AI deployers must inform individuals about the operation of AI systems used for emotion recognition or biometric categorization;

▸ AI providers must provide and publicly share a detailed summary of the training data used for general-purpose AI models;

▸ AI deployers who are also employers must notify workers’ representatives and affected employees about the use of high-risk AI systems in the workplace.

(ii) the right to object

As Article 21 of the GDPR outlines, individuals may object to processing their personal data, specifically when it comes to profiling.

Thus, the GDPR already provides users (of an AI systems/tool) with the ability to object to the use of their personal information, for example, in the case of training AI systems. The right to object ensures that individuals can prevent their data from being used in AI model development, especially when it involves profiling or automated decision-making.

Therefore, the existing GDPR framework sufficiently protects user privacy in the context of AI usage, eliminating the need for the AI Act to create a separate, additional mechanism for users to oppose using their personal data.

(iii) automated decision-making

Article 22 and Recital 71 of the GDPR grant individuals the right not to be subject to decisions made solely by automated processing (including profiling), particularly when these decisions have legal or similarly significant impacts.

The effective exercise of this right, including the eventual challenge of such automated decision, requires and entails human intervention. Building upon this, when it comes to high-risk AI systems, Article 14 of the AI Act provides for an additional layer of human oversight in the design and development especially of high-risk AI systems, to prevent risks to health, safety, or fundamental rights. Consequently, in terms of human intervention in automated decision-making, low or minimal-risk AI systems are subject only to the GDPR requirements.

(iv) risk assessment and documentation requirements

Article 35 of the GDPR requires a Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA) for high-risk data processing, such as large-scale profiling with AI (e.g., profiling of candidates/employees using an AI systems). Similarly, the AI Act mandates a conformity assessment for AI providers and a Fundamental Rights Impact Assessment (FRIA) for AI deployers.

FRIA requires evaluating AI system risks to individuals and determining mitigation strategies. While DPIA focuses on data processing impacts, FRIA assesses broader consequences of AI usage on individual rights. Article 27 para. (4) of the AI Act emphasizes their complementary nature, not as bureaucratic overlap but as distinct yet interconnected assessments addressing different aspects of AI implementation and its effects on fundamental rights.

The AI Act brings some novelties impacting personal data

Undoubtedly, the AI Act and the GDPR complete each other. However, given that the two legal frameworks do not regulate the same objects, they do not need the same approach. Thus, in certain respects, the AI Act offers a more flexible regime.

For example, the AI Act provides:

▸ that law enforcement authorities may use real-time remote biometric identification systems[2] in public spaces under exceptional circumstances, such as locating trafficking victims, preventing imminent threats, or identifying criminal suspects (e., Article 5 of the AI Act). These cases can be seen as exceptions to Article 9 of the GDPR, which generally prohibits the collection and processing of biometric data.

▸ the providers of high-risk AI systems may process special categories of personal data if it is strictly necessary for detecting and correcting biases (e., Article 10 of the AI Act). This processing must comply with the strict conditions set out in Article 9 of the GDPR.

▸ the re-use of sensitive data, such as genetic, biometric, and health data, within AI regulatory sandboxes[3] to support the development of systems with significant public interest (g., the health system). These sandboxes will be supervised by a dedicated authority (Article 59 of the AI Act).

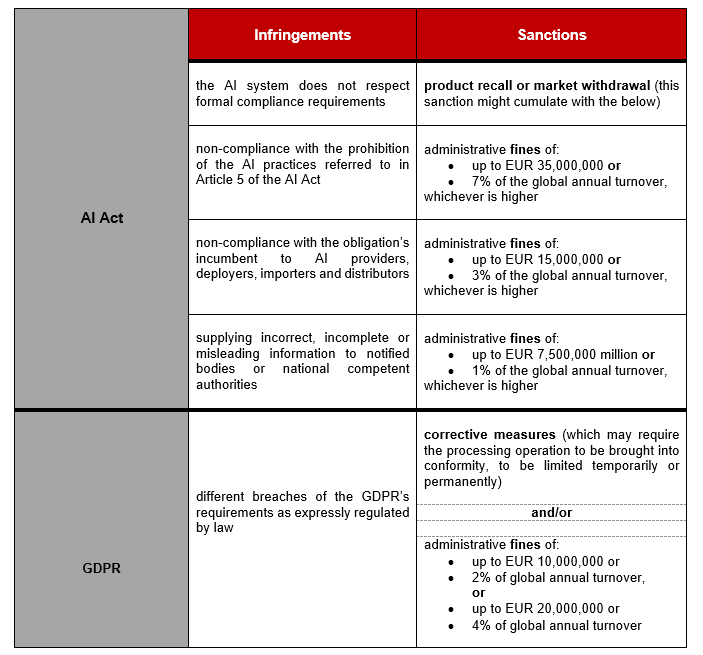

What about the sanctions?

Even if the two regulations complement each other, the sanctions for non-compliance with their provisions differ.

The main applicable sanctions are as follows:

Stay tuned for Part II of our article!

[[]“The impact of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) on artificial intelligence”, available at EPRS_STU(2020)641530_EN.pdf (europa.eu)

[2] Art. 3 item (42) of AI Act: “real-time remote biometric identification system” means a remote biometric identification system, whereby the capturing of biometric data, the comparison and the identification all occur without a significant delay, comprising not only instant identification, but also limited short delays in order to avoid circumvention.

[3] As per Article 57 of the AI Act, Member States shall ensure that their competent authorities establish at least one AI regulatory sandbox at national level, which shall be operational by 2 August 2026. (…) AI regulatory sandboxes shall provide for a controlled environment that fosters innovation and facilitates the development, training, testing and validation of innovative AI systems for a limited time before their being placed on the market or put into service pursuant to a specific sandbox plan agreed between the providers or prospective providers and the competent authority. Such sandboxes may include testing in real world conditions supervised therein.

[4] Art. 3 item (63) of AI Act: “general-purpose AI model” means an AI model, including where such an AI model is trained with a large amount of data using self-supervision at scale, that displays significant generality and is capable of competently performing a wide range of distinct tasks regardless of the way the model is placed on the market and that can be integrated into a variety of downstream systems or applications, except AI models that are used for research, development or prototyping activities before they are placed on the market.

[5] Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 June 2024 laying down harmonised rules on artificial intelligence and amending Regulations (EC) No 300/2008, (EU) No 167/2013, (EU) No 168/2013, (EU) 2018/858, (EU) 2018/1139 and (EU) 2019/2144 and Directives 2014/90/EU, (EU) 2016/797 and (EU) 2020/1828 (Artificial Intelligence Act), available at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32024R1689.

[6] Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation), available at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/679/oj.